Reverse Engineering Expected Goals

In this post we are going to look again at the 2018-2019 Premier League season and try to reverse engineer bookmakers odds in order to obtain the expected goals for each match. Then, we are going to try to improve on these models and reduce our reliance on bookmakers odds. In the process, I will present two ways of implementing the Poisson regression in Python - one from scratch and one based on the the statsmodel library.

The expected goals is a very important number for compiling odds because, if plugged into the Poisson distribution, it gives is the possibility to compute any goal-based markets.

We are going to use publicly available data, downloaded from here. In case the link disappears, here is a local copy of the csv file used for this analysis. The explanation for the columns can be found here

Reverse Engineering Expected Goals Using Direct Optimization

We are looking independently at each line, the match odds for home-draw-away and over-under, and optimize the mean squared error loss function for each match. We are going to consider the match goals as Poisson distributed.

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

from scipy.stats import poisson

from scipy.optimize import minimize

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

# https://datahub.io/sports-data/english-premier-league#readme

data = pd.read_csv("season-1819_csv.csv") # todo: add index on team names!

rows = len(data)

teams = int(np.sqrt(rows)) + 1

###

# BbAvH = Betbrain average home win odds

# BbAvD = Betbrain average draw win odds

# BbAvA = Betbrain average away win odds

# BbAv>2.5 = Betbrain average over 2.5 goals

# BbAv<2.5 = Betbrain average under 2.5 goals

# FTHG and HG = Full Time Home Team Goals

# FTAG and AG = Full Time Away Team Goals

###

data = data[['HomeTeam', 'AwayTeam','BbAvH', 'BbAvD', 'BbAvA', 'BbAv>2.5', 'BbAv<2.5', 'FTHG', 'FTAG']]

### xG reverse engineering

def hda_ou25(xGH, xGA):

h_distrib = np.array([poisson.pmf(x, xGH) for x in range(0, 10)])

a_distrib = np.array([poisson.pmf(x, xGA) for x in range(0, 10)])

ret = [0, 0, 0, 0, 0]

for i in range (0, len(h_distrib)):

for j in range (0, len(a_distrib)):

p = h_distrib[i] * a_distrib[j]

# hda part

if i > j:

ret[0] += p

elif i == j:

ret[1] += p

elif i < j:

ret[2] += p

# ou 2.5 part

if i + j > 2.5:

ret[3] += p

elif i + j < 2.5:

ret[4] += p

return 1/np.array(ret)

def loss_hdaou(xG,hda_ou_target):

v = hda_ou25(xG[0], xG[1]) - hda_ou_target

return np.dot(v, v) # square the error

def compute_xg(row):

hda_ou_target = np.array([row[c] for c in ['BbAvH', 'BbAvD', 'BbAvA', 'BbAv>2.5', 'BbAv<2.5']]).flatten()

ret = minimize(loss_hdaou, [1.25, 1.25], args=(hda_ou_target), method='COBYLA').x

return pd.Series(ret, index=['xGH', 'xGA'])

xg = data.apply(compute_xg, axis=1)

data['xGH_optim'] = xg['xGH']

data['xGA_optim'] = xg['xGA']

Reverse Engineering Expected Goals From Bookmakers Odds Using The Poisson Regression

The next step is to do exactly the same thing, but this time using Poisson regression. Poisson regression is very useful for things like counts. It aims to compute a set of regression coefficients such that lambda = sum(regression_coef_i * predictor_variable_i). Poisson regression is solved through the Maximum Likelihood Estimate method, as shown below:

# poisson regression:

def poisson_compute_xg(betas, factors, goals):

# compute the lambda for each row based on the proposed betas

lmbdas = np.dot(betas, factors.T)

if(np.min(lmbdas) <= 0e-5):

print("violated constraint")

return 1e10

# compute the probability for obtaining the observed counts (goals)

# given the lambda

psn = [poisson.pmf(g, l) for (g,l) in zip(goals, lmbdas)]

# return the MLE sum of logarithms

return -np.sum(np.log(psn))

def poisson_regress(X, y):

factors = X.to_numpy()

# start with 1 for all factors

betas = [1] * factors.shape[1]

# MLE

return minimize(poisson_compute_xg, betas, args=(factors, y), method='cobyla').x

# transform from odds to probabilities to get a better regression

X = 1/data[['BbAvH', 'BbAvD', 'BbAvA', 'BbAv>2.5', 'BbAv<2.5']]

y_h = data['FTHG']

y_a = data['FTAG']

betas_h = poisson_regress(X, y_h)

betas_a = poisson_regress(X, y_a)

data['xGH_regress'] = np.dot(X, betas_h)

data['xGA_regress'] = np.dot(X, betas_a)

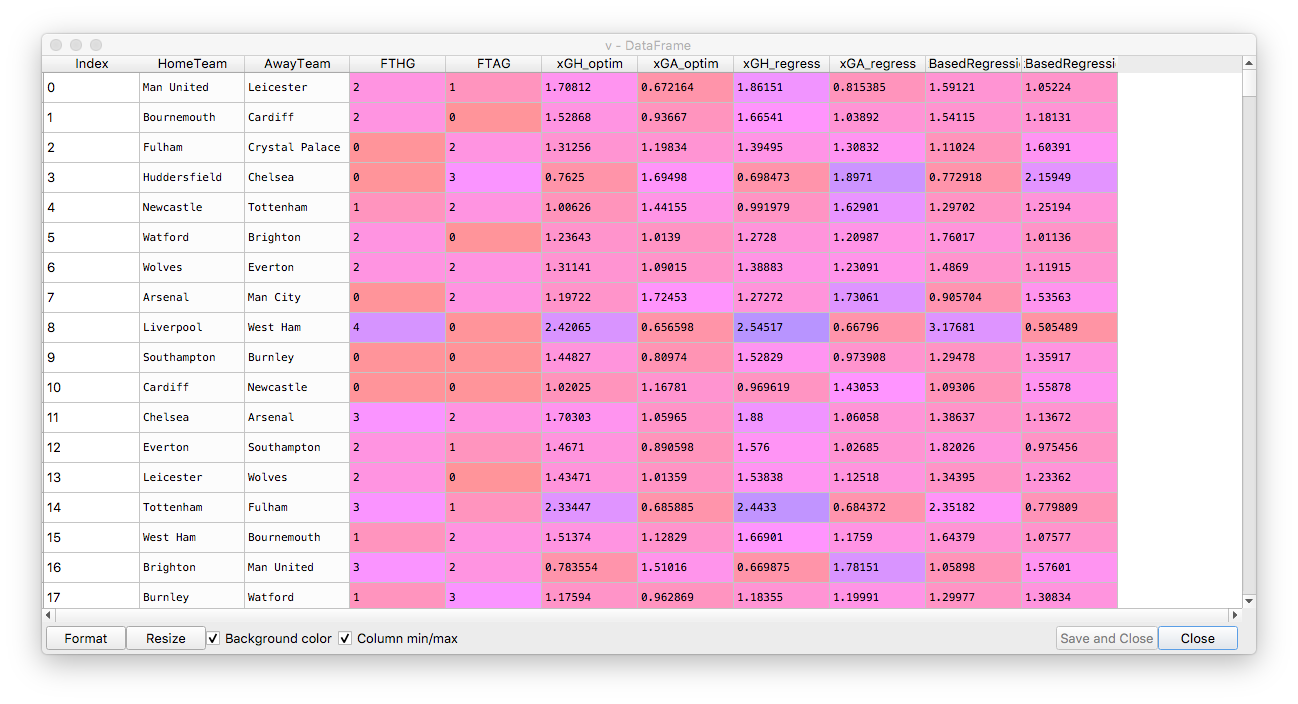

The results for the two methods are highlighted in the dataframe below:

Now let’s look at the RMSE for the two methods. For in-sample RMSE we obtain lower RMSE for the Poisson regression. However, the difference is very small:

rmse_optim = np.sqrt(np.sum((data['FTHG'] - data['xGH_optim']) ** 2 + (data['FTAG'] - data['xGA_optim']) ** 2) / len(data))

rmse_regress = np.sqrt(np.sum((data['FTHG'] - data['xGH_regress']) ** 2 + (data['FTAG'] - data['xGA_regress']) ** 2) / len(data))

rmse_optim

Out[190]: 1.5902709407482063

rmse_regress

Out[191]: 1.5836188549138615

For out-of-sample RMSE, we usually have lower RMSE for Poisson regression, but this is not always the case. Again, the difference is small and we can consider the two methods roughly equivalent.

X['xGH_optim'] = data['xGH_optim']

X['FTHG'] = data['FTHG']

X_train_h, X_test_h, y_train_h, y_test_h = train_test_split(X, y_h)

betas_h = poisson_regress(X_train_h[['BbAvH', 'BbAvD', 'BbAvA', 'BbAv>2.5', 'BbAv<2.5']], y_train_h)

result = np.dot(X_test_h[['BbAvH', 'BbAvD', 'BbAvA', 'BbAv>2.5', 'BbAv<2.5']], betas_h)

from sklearn.metrics import mean_squared_error

rmse_optim = np.sqrt(mean_squared_error(X_test_h['FTHG'], X_test_h['xGH_optim']))

rmse_regress = np.sqrt(mean_squared_error(X_test_h['FTHG'], result))

rmse_optim

Out[196]: 1.162618442066351

rmse_regress

Out[197]: 1.1526039105430579

Computing the Expected Goals Using Team Ranking

In Odds And Models, we used a factor-based system for determining the expected goals. In this post we will take a different approach and create a team rank based model for the same thing. We will start with a basic model, lambda = b0 + b1 * home_team_rank + b2 * away_team_rank. Out of laziness, I will only do the in-sample analysis which has the potential to skew the results quite heavily.

For ranking the teams, we are going to use the power function and define the probability of one team winning as p(x>y) = x / (x+y) = rank(t1) / (rank(t1) + rank(t2)), where the ranks for each team are the variables we want to compute using MLE.

For encoding the result of the winning team I tried two different definitions:

HomeWins = (X['FTHG'] > X['FTAG']).to_numpy().flatten()- simply assigns1to the variable if the home team wins or draws, to count for the home field advantage.HomeWins = np.clip(zscore((X['FTHG'] - X['FTAG']).to_numpy()), -0.5, 0.5) + 0.5- spreads a little bit the unclear wins while taking into account the home team advantage (zscore will normalize for home team advantage).

I was surprised to observe that the second function produces more extreme results for the ranking, so we will keep the first definition of a win for this exercise.

# starting with fresh data

data = pd.read_csv("season-1819_csv.csv")

# only keep in our dataframe the interesting variables

X = data[['HomeTeam', 'AwayTeam', 'FTHG', 'FTAG']]

# power_function

# p(x>y) = x / (x+y) = rank(t1) / (rank(t1) + rank(t2))

# make sure we don't miss any team names

teams = X['HomeTeam'].combine_first(X['AwayTeam']).unique()

teams = pd.DataFrame(index=teams)

# initialize the team ranks

teams['Rank'] = 0.5

# give an advantage to the away

HomeWins = (X['FTHG'] > X['FTAG']).to_numpy().flatten()

#HomeWins = np.clip(zscore((X['FTHG'] - X['FTAG']).to_numpy()), -0.5, 0.5) + 0.5

def mle_prob(ranks):

teams['Rank'] = ranks

h = teams.loc[X['HomeTeam']].to_numpy().flatten()

a = teams.loc[X['AwayTeam']].to_numpy().flatten()

denom = h + a + 1e-5

ph = h / denom

pa = a / denom

r = -np.sum(np.log(ph * HomeWins + pa * (1-HomeWins)))

return r

# bounds between 0 and 1

teams['Rank'] = minimize(mle_prob, list(teams['Rank']), bounds=Bounds([1e-5] * len(teams), [1] * len(teams))).x

teams.sort_values('Rank', ascending=False)

teams['LogRank'] = np.log(teams['Rank'])

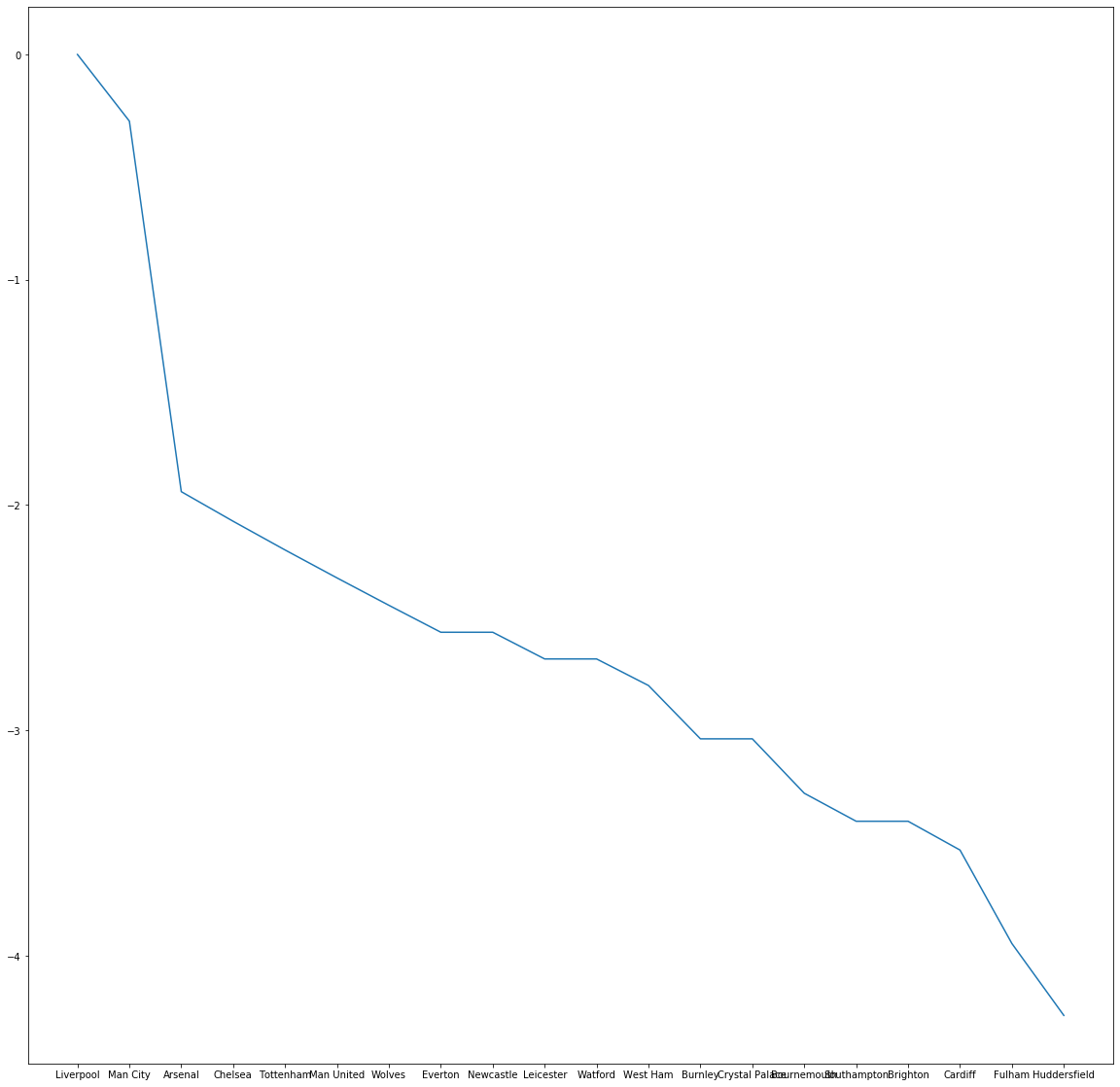

The results for our ranks are as follows:

teams.sort_values('Rank', ascending=False)

Out[183]:

Rank LogRank

Liverpool 1.000000 0.000000

Man City 0.743936 -0.295801

Arsenal 0.143627 -1.940538

Chelsea 0.125926 -2.072060

Tottenham 0.110863 -2.199463

Man United 0.097941 -2.323390

Wolves 0.086728 -2.444978

Everton 0.076957 -2.564509

Newcastle 0.076957 -2.564509

Leicester 0.068357 -2.683007

Watford 0.068357 -2.683007

West Ham 0.060753 -2.800934

Burnley 0.047952 -3.037547

Crystal Palace 0.047952 -3.037547

Bournemouth 0.037663 -3.279067

Southampton 0.033260 -3.403410

Brighton 0.033260 -3.403410

Cardiff 0.029270 -3.531198

Fulham 0.019328 -3.946205

Huddersfield 0.014049 -4.265229

Since the obtained the rank values fall very quickly very fast, we logged them to get smoother results.

# put data

X['HomeRank'] = (teams.loc[X['HomeTeam']]['LogRank']).to_numpy()

X['AwayRank'] = (teams.loc[X['AwayTeam']]['LogRank']).to_numpy()

RegressionData = pd.DataFrame(index=X.index)

RegressionData = X[['HomeRank', 'AwayRank']]

RegressionData['Intercept'] = 1

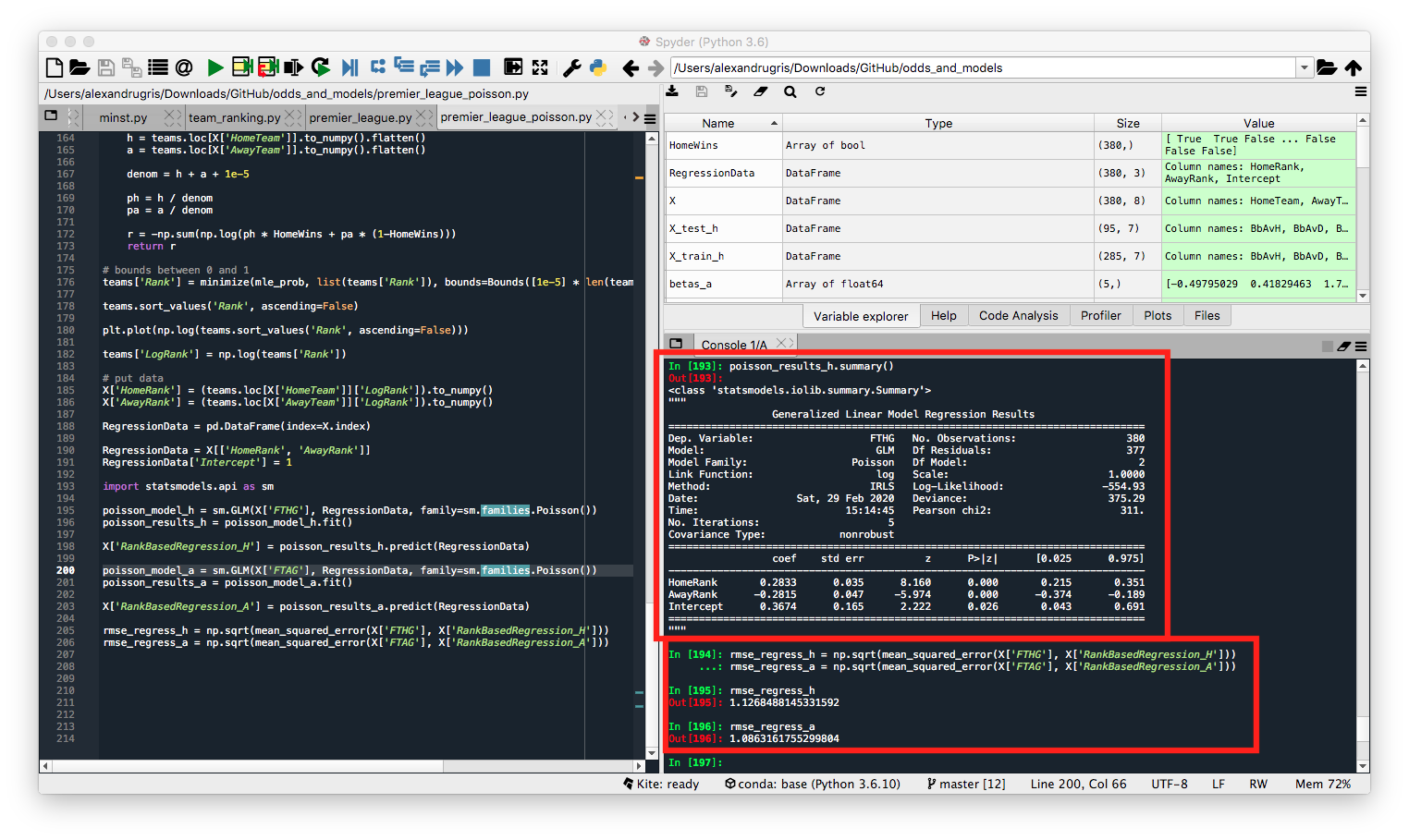

For the next step we will do again a Poisson regression to get the expected goals lambda, but this time we will use the statsmodel.api package since we have already demonstrated above how Poisson regression works if we are to do it manually. We will predict for both home and away.

import statsmodels.api as sm

poisson_model_h = sm.GLM(X['FTHG'], RegressionData, family=sm.families.Poisson())

poisson_results_h = poisson_model_h.fit()

X['RankBasedRegression_H'] = poisson_results_h.predict(RegressionData)

poisson_model_a = sm.GLM(X['FTAG'], RegressionData, family=sm.families.Poisson())

poisson_results_a = poisson_model_a.fit()

X['RankBasedRegression_A'] = poisson_results_a.predict(RegressionData)

rmse_regress_h = np.sqrt(mean_squared_error(X['FTHG'], X['RankBasedRegression_H']))

rmse_regress_a = np.sqrt(mean_squared_error(X['FTAG'], X['RankBasedRegression_A']))

We can now observe the regression coefficients, the p-value for each coefficient showing that all features are relevant, as well as the RMSE for home and away expected goals vs real goals. The RMSE is better than the previous two models, but I expect this is due to the dataset as well as the in-sample regression test:

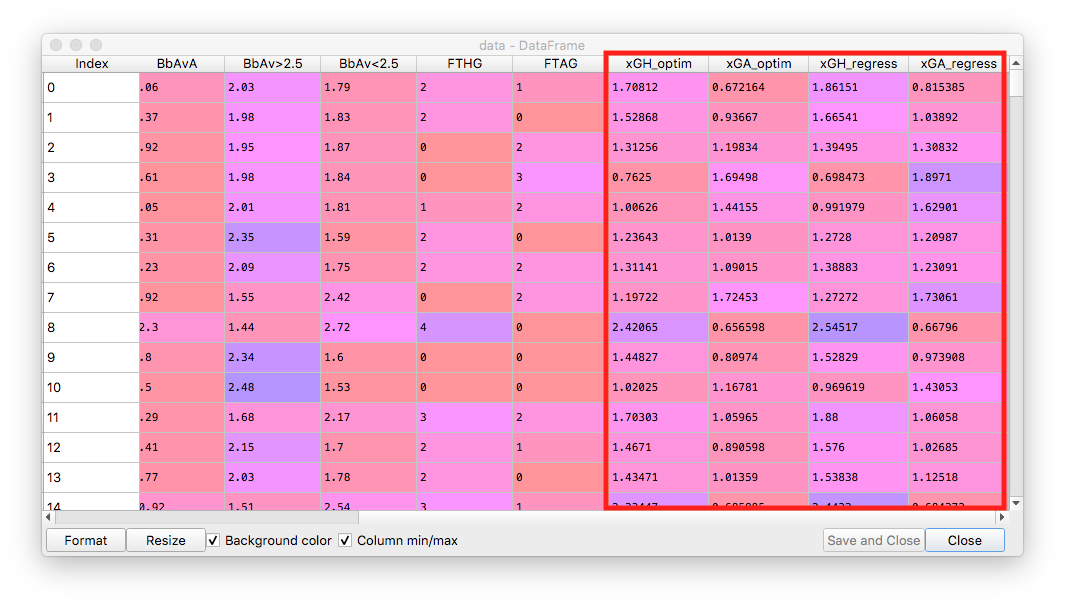

And below the full view of the regression parameters and expected goals:

Putting all 3 methods side by side, we can see that even this simple rank-based model, oblivious of bookmakers odds, has very good potential and it is worth improving further on.