Introduction to Cryptography (Part 3)

This is the third part of Introduction to Cryptography. The post covers the Java APIs that implement the same algorithms that we spoke about in the previous posts, symmetric and asymmetric encryption, as well as digital signatures. We also talk a little bit about password security and the principle behind rainbow tables.

Java APIs, Encryption, Decryption, Signatures

I am going to exemplify here the concepts from the previous posts using the Java Cryptography Extensions (JCE). Most programming languages have similar cryptographic support. JCE revolves around the following classes:

KeyGenerator- key generator for symmetric encryptionSecretKey- the generated symmetric keySecureRandom- cryptographically secure random number generatorIvParameterSpec- initialization vector for the algorithm (remember that the Cypher Block Chaining (CBC) requires an init vector)KeyPairGenerator- key generator for asymmetric encryptionPublicKey- the public keyPrivateKey- the private keyCipher- perform the work of the symmetric / asymmetric encryptionSignature- performs the work of the signature algorithmCipherInputStream- input stream for decryptionCipherOutputStream- output stream for encryption

The current Java implementation, Java 14, supports the following algorithms: link

/**

* Encrypting with symmetric encryption. Only the necessary information is shared with this method.

* In a production scenario, these would come from a secrets database

* @param msg - the message

* @param algorithm - the algorithm

* @param key - the secret key

* @param iv - the initialization vector

*/

static byte[] encryptAES(String msg, String algorithm, SecretKey key, IvParameterSpec iv)

throws NoSuchPaddingException,

NoSuchAlgorithmException,

InvalidAlgorithmParameterException,

InvalidKeyException {

Cipher c = Cipher.getInstance (algorithm);

c.init (Cipher.ENCRYPT_MODE, key, iv);

var output = new ByteArrayOutputStream ();

try(var cos = new CipherOutputStream (output, c)){

cos.write (msg.getBytes ());

}

catch (IOException exx){

exx.printStackTrace ();

}

return output.toByteArray ();

}

/**

* The decryption function

* @param encrypted - the text to be decrypted

* @param algorithm - the algorithm used

* @param sk - the secret key

* @param iv - the initialization vector

* @return

*/

static String decryptAES(byte[] encrypted, String algorithm, SecretKey sk, IvParameterSpec iv)throws

InvalidAlgorithmParameterException,

InvalidKeyException,

NoSuchPaddingException,

NoSuchAlgorithmException {

Cipher c = Cipher.getInstance (algorithm);

c.init (Cipher.DECRYPT_MODE, sk, iv);

try(var bais = new ByteArrayInputStream(encrypted);

var cis = new CipherInputStream (bais, c)){

return new String(cis.readAllBytes ());

} catch (IOException e) {

e.printStackTrace ();

}

return null;

}

/**

* Start here

*/

static void test_symmetricJCE()

throws NoSuchAlgorithmException,

NoSuchPaddingException,

InvalidAlgorithmParameterException,

InvalidKeyException {

// Generate the secret key

KeyGenerator keyGen = KeyGenerator.getInstance ("AES");

keyGen.init (256);

SecretKey sk = keyGen.generateKey ();

assert sk.getAlgorithm ().equals ("AES"); // algorithm

assert sk.getEncoded ().length == 32; // key size in bytes

// Create an instance of the AES cypher, with CBS and

// a padding to fill the missing bytes at the end of the message.

// Generate the initialization vector for our CBC.

// We use the block size from the algorithm for the size of our iv

SecureRandom sr = new SecureRandom ();

byte[] ivbytes = new byte[Cipher.getInstance ("AES/CBC/PKCS5Padding").getBlockSize ()];

sr.nextBytes (ivbytes);

IvParameterSpec iv = new IvParameterSpec (ivbytes);

// encrypt and decrypt

var msg = "This is my first long message encrypted with AES / CBC";

var encrypted = encryptAES(msg, "AES/CBC/PKCS5Padding", sk, iv);

var decrypted = decryptAES(encrypted, "AES/CBC/PKCS5Padding", sk, iv);

assert msg.equals (decrypted);

}

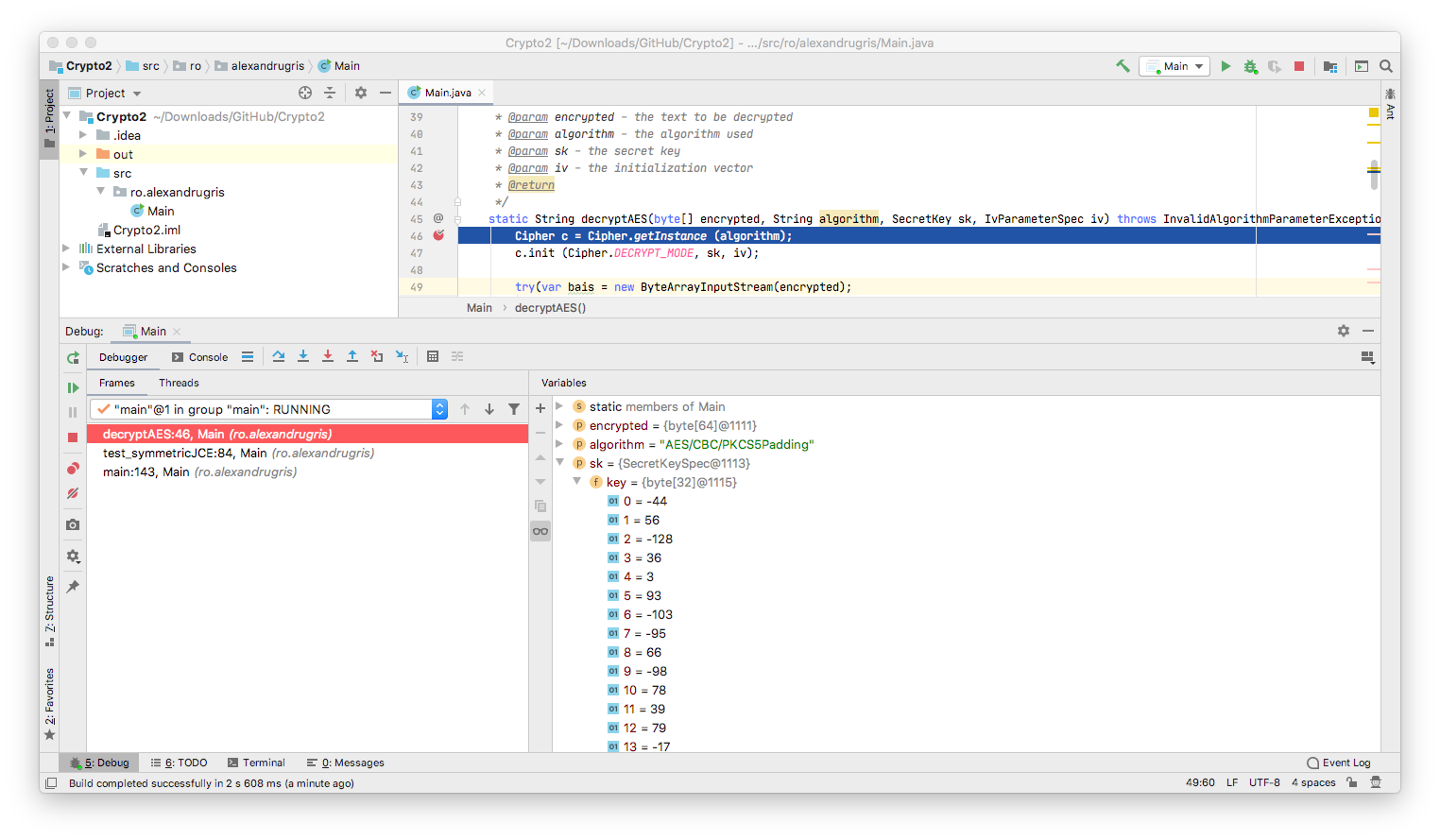

In the picture below we can observe that the secret key is just an array of bytes, similar to what we have seen when we implemented the algorithm from scratch, in the previous post.

It is important to note that, if two messages start with the same bytes, the first bytes in the encrypted string for both of them will be the same, if we use the same initialization vector. Therefore, it is good practice to change the initialization vector with each message.

For the asymmetric encryption, the process is very similar. The only differences are in the methods we call on the Cipher class. Since Cipher works iteratively on blocks, to encrypt / decrypt with RSA which is not a block cipher, we need to invoke Cipher::doFinal() on the cipher, as if the whole message is a single block. Example below.

private static void test_asymmetricJCE() throws

NoSuchAlgorithmException,

NoSuchPaddingException,

InvalidKeyException,

BadPaddingException,

IllegalBlockSizeException {

var msg = "This is my first long message encrypted with RSA";

KeyPairGenerator kg = KeyPairGenerator.getInstance ("RSA");

kg.initialize (2048);

var kp = kg.generateKeyPair ();

// encrypt

var c1 = Cipher.getInstance ("RSA/ECB/PKCS1Padding");

c1.init (Cipher.ENCRYPT_MODE, kp.getPrivate ());

byte[] encrypt = c1.doFinal (msg.getBytes ());

// decrypt

var c2 = Cipher.getInstance ("RSA/ECB/PKCS1Padding");

c2.init (Cipher.DECRYPT_MODE, kp.getPublic ());

var ret = new String(c2.doFinal (encrypt));

assert ret.equals (msg);

}

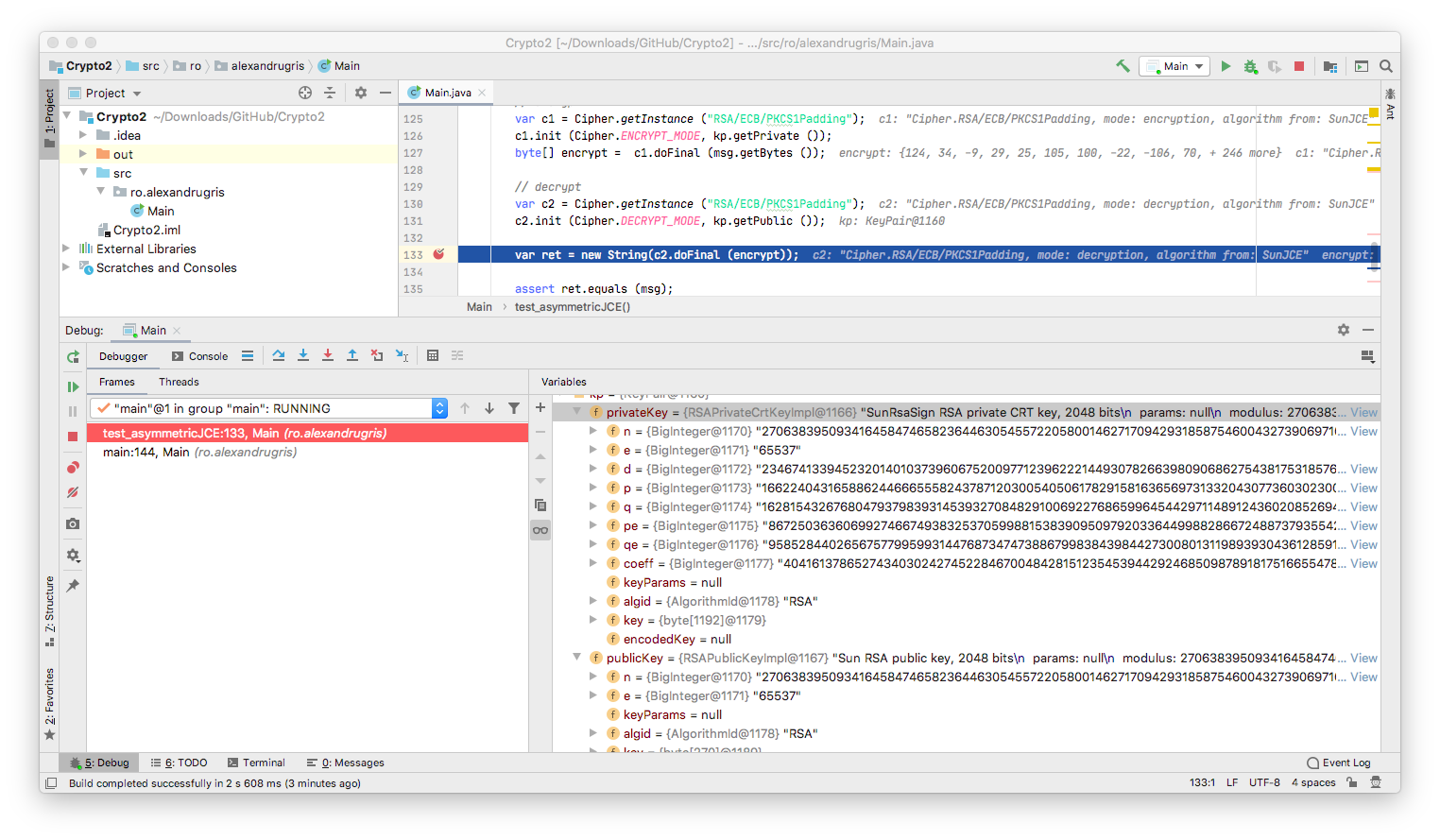

In the picture below we can see the public / private key pair expanded. We observe the same elements that we spoke about when we implemented the algorithm from scratch, in the previous post:

pandqmy private two large prime numbersn = p*q, the modulo, sharede, the public exponent - shared (encrypting) - the requirement for this is to be relatively prime top-1andq-1. A commonly used exponent is65537since it is a prime number all together .d, the private exponent - shared (decrypting) -

Several important notes:

-

KeyPairGenerator::generateKeyPair()might take several seconds. Therefore, it is better to store / read the keys from a secure key store. -

The RSA algorithm is generally slow so, in practice, it is used to

encrypt -> transmit -> decrypta key that will be used further with a symmetric encryption algorithm. In our case, we would have had encrypted theSecretKeyfrom the first example, transmit it over the wire, then use thatSecretKeyto encrypt the rest of the communication.

Now, let’s use the private / public key pair to sign a message:

private static void test_signaturesJCE() throws NoSuchAlgorithmException, InvalidKeyException, SignatureException {

var msg = "This is my first long message signed with RSA";

KeyPairGenerator kg = KeyPairGenerator.getInstance ("RSA");

kg.initialize (2048);

var kp = kg.generateKeyPair ();

// sign

var sigSign = Signature.getInstance ("SHA256withRSA");

sigSign.initSign (kp.getPrivate ());

sigSign.update (msg.getBytes ());

var sig = sigSign.sign ();

// verify

var sigVerify = Signature.getInstance ("SHA256withRSA");

sigVerify.initVerify (kp.getPublic ());

sigVerify.update (msg.getBytes ());

var ret = sigVerify.verify (sig);

assert ret;

}

Authentication and Authorization

The first thing to know about passwords is that you never store them in clear text. More precisely you don’t even need to store the full password in any form. Since the verification is just one way, it is enough to store a password hash that is checked against every time the password is entered. The most basic form for checking whether a site keeps passwords in clear text is so see if they offer a password retrieval function. If they do, better close the account and never use that password again.

A more common form of attack are leaked password hashes. We could use dictionary attacks to match hashes to known passwords and that would lead to dictionaries being extremely large. A method that trades the size of the dictionary for a bit of additional computation is the rainbow table. The principle is to compute a series of chains, pairs of (starting password, ending hash). Each chain is, in fact, like (starting password -> hash -> new password -> hash … -> ending hash), but, since we know the transform function from password to hash and then from hash to a new potential password, we don’t need to store the intermediate results. We don’t want to reverse the hash, but to try to find a collision. What is needed for rainbow table to work are (a) a leaked the password hash and (b) the algorithm used for obtaining that hash. The algorithm starts by identifying which chain the leaked hash belongs to and then, iterating through the chain, find a password that generates that very same hash.

Here is a very basic example of the principle, written in Java. The code is based on this excellent article.

package ro.alexandrugris;

import java.nio.charset.StandardCharsets;

import java.util.HashMap;

public class Main {

// compute password -> hash -> password chain

// for simplicity, in our case, hash -> password function is just the identity function

static String hash(String s){

byte[] str = s.toUpperCase ().getBytes (StandardCharsets.US_ASCII);

byte[] n_pass = new byte[str.length];

// a very basic and a very bad hash function

for(int i = 0; i < str.length; i++){

var x = str[i] - 'A';

var hash = (int)(2000 * (x * 1.618 % 1));

n_pass[i] = (byte)(hash % ('A' - 'Z') + 'A');

}

return new String (n_pass);

}

static String computeChain(String start){

// chains of 4, because our hash function is very weak and it loops very quickly.

for (int i = 0; i < 4; i++){

start = hash (start);

}

return start;

}

static String guessPassword(String initial, HashMap<String, String> map){

String hash = initial;

// N = 100 tries

for(int i = 0; i < 100; i ++){

// 3. try to find the hash in the rainbow table

var chain = map.get (hash);

// 4. if the hash was not found, compute the next password and the next hash

if(chain == null){

hash = computeChain (hash);

}

else{

// 5. the hash was found, which means I found the chain

// start from the beginning of the chain,

// compute the hash.

// When the hash is equal to the hash I want to break,

// that is a working password!

while(true){

var next = computeChain (chain);

if(next.equals (initial))

return chain;

else

chain = next;

}

}

}

return null; // not found

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

// 1. compute rainbow table, a hashmap of <hash, starting point>

HashMap<String, String> myRainbowTable = new HashMap<> ();

String[] startingPoints = {

"HELL",

"BUBU",

"FUFU",

"ROCK"

};

for (var s : startingPoints){

myRainbowTable.put (computeChain (s), s);

}

// 2. obtain the password hash we want to reverse

var passHash = "WJGG";

System.out.println (guessPassword(passHash, myRainbowTable));

}

}

The interesting thing to observe is how an increased password complexity increases exponentially the complexity of generating and searching the rainbow table. It also shows that for salted passwords an attacker will have a harder time reversing it as it has to start by generating the rainbow table for those specific salts. The salt itself, a string pre-pended or appended to the password, does not need to be protected. It can be stored in plain text in the passwords table, but, for good protection, it should different for every user.

To make it unfeasible for an attacker to brute force our passwords, the algorithm used to compute the hash should be (a) irreversible (b) take a long time. The application only runs this algorithm for each login, but the attacker would have to run it for every password retry. The recommended approach is called PBKDF and the general concept is called key stretching.

static String passwordHash(String password, String salt, int iterations, int keyLength)

throws NoSuchAlgorithmException, InvalidKeySpecException {

SecretKeyFactory f = SecretKeyFactory.getInstance ("PBKDF2WithHmacSHA1");

// iterations should be minimum 1000, preferably 10000

// should be increased as computers become more powerful

// the idea is to have a time-consuming operation

// that makes it computationally hard for the attacker to brute force the password

KeySpec ks = new PBEKeySpec (password.toCharArray (), salt.getBytes (), iterations, keyLength);

SecretKey s = f.generateSecret (ks);

return new String(Base64.getEncoder ().encode (s.getEncoded ()));

}